Gospel, Blues and Jazz Pioneers:

Early Twentieth Century, Harlem Renaissance and Beyond

African slaves brought many skills with them during their unwilling journey to America; i.e., their knowledge of agriculture, culinary techniques, metallurgy and other crafts to name just a few. African Slaves also “came to America with the syncopated rhythms and melodies of Africa. They merged these with the European adaptations of plantation owners and created a new music, a music that evolved from field chants to spirituals to ragtime and ultimately to blues, jazz and gospel…During the period when W. C. Handy was plying the Mississippi Delta in search of the blues, Scott Joplin was refining another of America’s original musical forms, ragtime. His syncopated piano style and numerous ragtime compositions earned him the distinction as the king of rag. The emergence of blues and ragtime in the first decade of the 1900s captivated the entire Country. Also, in the first decade of the century, a young cornet player in New Orleans named Buddy Bolden was taking a different direction. His improvisations on the Cornet were mirrored by most of the young musicians of the city. Pianist Jelly Roll Morton and cornetist Joe “King” Oliver left New Orleans and took the music to Chicago, where, during the second decade of the century, jazz found a fertile environment, as did blues and gospel, and exploded across America. It also spread rapidly throughout Europe when Mobile, AL native James Reese Europe took his 369th Infantry Regiment Band to Europe during World War I and brought African American music to a world stage.”1 It may be more accurate to say that Europe primarily introduced Europe to blues, ragtime and jazz. To be more precise, the Fisk Jubilee Singers were the first to introduce Europe to the “new music of America”, African American Spirituals, during their enormously successful seven-month tour in 1873 that began in England. Their concert tour also included venues in Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

It’s no surprise the extent to which the paths of African American leaders, historians, singers, songwriters and poets intersected throughout American history. From W. E. B. Du Bois waxing poetic whenever he gazed upon his beloved Jubilee Hall at Fisk University and his love of African American spirituals; to Frederick Douglas embracing and nurturing the talents of poets Langston Hughes and James Weldon Johnson, and also encouraging the music of the legendary songwriter Wil Marion Cook; to Martin Luther King, Jr. requesting the performance of Mahalia Jackson at many of his speeches. Recall the historic “March on Washington” in 1963 and Dr. King’s “I have a dream speech.” At his request, Mahalia sang “I’ve Been ‘Buked, and I’ve Been Scorned” before he rose to the podium to speak. According to first hand reports, in the middle of Dr. King’s speech, Mahalia shouted to him from the rear, “Tell them about the dream, Martin!” The rest is history.

Rev. Dr. Thomas A. Dorsey

Father of Gospel Music

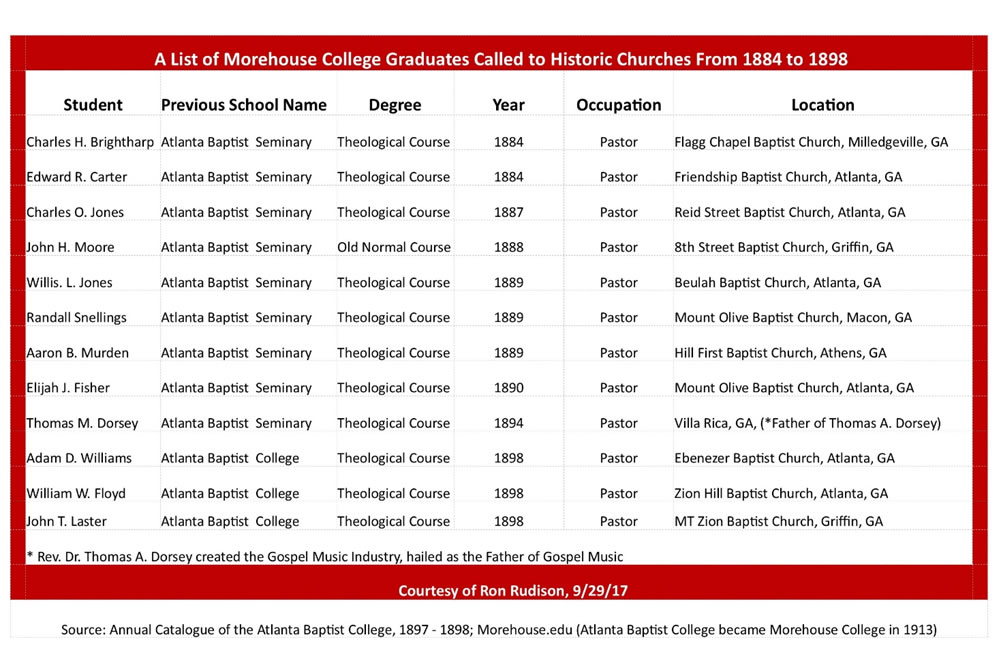

Thomas Andrew Dorsey was born in Villa Rica, GA on July 1st, 1889. His parents were Rev. Thomas Madison Dorsey and Etta Plant Dorsey. The elder Dorsey graduated from Morehouse College in 1884, formerly the Augusta Baptist Institute. Rev. Dorsey was widely acknowledged as an itinerant preacher during the early 1900s. He was accompanied by his wife Etta while ministering to sharecroppers, farmers and laborers in the areas surrounding Villa Rica. Etta also was his “Minister of Music,” carrying a portable organ with her as she punctuated Rev. Dorsey’s sermons with hymns of the day. They must have presented an impressive image to the congregants to whom they ministered, the “Morehouse educated preacher,” “dressed to the nines,” sporting a cane, with his musically gifted spouse and inquisitive Young son, Junior, in tow. Thomas M. Dorsey was among a cadre of men at Morehouse College who embodied the concept of “A Morehouse Man,” early leaders of the African American community who shared their skills and expertise throughout the city of Atlanta, the state of Georgia, the United States and internationally. These men led historic churches dating to the late-1800s that still are vital to their respective communities. One of Thomas M. Dorsey’s contemporaries, Rev. Adam D. Williams, was the founding Pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, father-in-Law of Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr., and Maternal Grandfather of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Leader of the Civil Rights Movement in America). Early Morehouse College graduates also would become doctors, lawyers, teachers, school administrators, political leaders and more. Dorsey, although not an historic figure in that sense, was more than an itinerant preacher; he was a “Morehouse Man” who spread the gospel to an appreciative audience in the Villa Rica, GA area, and possessed parenting skills that shaped the character of a son who was to leave a legacy of sacred music that inspired the world.

Etta Dorsey was previously married to Charles Spencer, a railroad employee who tragically died while boarding a train. Michael Harris speculates in his “the Rise of Gospel Blues” that Etta may have obtained a cash settlement from the railroad company after her former husband’s death, and that she used these funds to invest in farmland and city lots in Villa Rica. Her new husband, Thomas M. Dorsey, at one point invested his labor in his wife’s dream of being an entrepreneur. Rev. Thomas M. Dorsey preached and taught school around the Villa Rica area during the 3 or 4 months of the “off season” from planting and harvesting crops. Farming did not work out as a means of supporting the family, so they moved to nearby Atlanta in 1908. Atlanta was a beacon that attracted many African American professionals and musicians at the turn of the 20th Century. The young Thomas A. Dorsey did not fare well in the city schools of Atlanta. As a young teenager, he instead chose to work at the 81 Theatre, a vaudeville venue that hosted artists such as “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith and the pianists that accompanied them. The young Dorsey served soft drinks and popcorn. He became an avid student of piano and the blues while listening to and catching performances by “Ma” Rainey and quizzing local pianists at the 81 Theatre. He became proficient enough at piano to play house parties in Atlanta. The musical influences of Dorsey’s mother playing religious hymns on organ and the “barrelhouse blues” pianists at the 81 Theatre played an integral role in the development of Thomas A. Dorsey’s musical gifts. The twin ministries of his mother’s music and his father as itinerant pastor would prepare him to overcome the trials that awaited him later in life. Another mentor of the young Dorsey was his mother’s brother in law, C M Hindsman. He taught school in Villa Rica, Ga and also taught “shape note singing,” both at his father’s Mt. Prospect Baptist Church. Hindsman would later be honored as a landmark educator in Villa Rica with an elementary school named after him, Glanton-Hindsman Elementary School.

A look at selected economic and political events during the early years of Thomas A. Dorsey and his family are worth noting:

- A year before Thomas M. Dorsey’s graduation from Morehouse College, America experienced the “Great Depression of 1893.” Full recovery would not begin until 1897.

- In September 1906, 25 African Americans killed during the “Atlanta Race Riots.”

- “In 1907, Georgia Governor Hoke Smith, who had campaigned promising to disenfranchise black voters, signed an act that would amend Georgia’s constitution and impose a literacy test as a requirement for voting.”

- Georgia farms experienced a softening of cotton prices beginning 1900. The bottom fell out of the cotton market in 1915 with the introduction of the boll weevil into the United States.

- The population of Atlanta increased to 154,839 in 1910, up from 89,872 in 1900; e.g., a 72% increase during the 1st decade of the century, another 30% by 1920. (U.S. Census Report)

- On July 28, 1914, World War I (WWI) begins with the declaration of war by Austria-Hungary against Serbia. The United States enters WWI by declaring war against Germany on April 6, 1917.

- By 1915, The Chicago Defender had become the most influential African American newspaper in the country. “The newspaper was read extensively in the South. Black Pullman porters and entertainers were used to distribute the paper across the Mason/Dixon line. The paper was smuggled into the south because white distributors refused to circulate The Defender and many groups such as the Ku Klux Klan tried to confiscate it or threatened its readers. The Defender was passed from person to person, and read aloud in barbershops and churches. It is estimated that at its height each paper sold was read by four to five African Americans, putting its readership at over 500,000 people each week.” The newspaper urged African Americans to flee the oppression and limited job opportunities of the south, come north to ample job openings, higher wage and better living conditions. By their estimates, over 1.5 million African Americans left the south and migrated to northern cities between 1915 and 1925. “At least 110,000 came to Chicago alone between 1916-1918, nearly tripling the city’s black population.”

Dorsey left Atlanta in 1916, finally settling in Chicago, IL. The “Great Migration” of African Americans was in its infancy. Early Blues and Jazz Musicians eagerly raced to Chicago, navigating the “Blues Highway” from New Orleans, the Mississippi Delta and points in between. Most were attracted by the prospects of an evolving “music scene” in Chicago and escape from oppressive conditions in the South. Thomas Dorsey immersed himself in the excitement of the jazz and blues offerings that were in abundance. He even took a course in musical arranging and composition to give him an edge, separating himself from other talented musicians who could read music but not write it. Dorsey’s blues career was launched by his first blues song in 1923, “I Want a Daddy I Call My Own;” however, he wrote his first Gospel Song, “If I don’t Get There,” in 1921. He subsequently was re-united with Ma Rainey and formed the Wild Cats Jazz band that accompanied her on tour. Thomas Dorsey, recording as “Georgia Tom,” also teamed up with “Tampa Red” Whitaker and recorded a raucous blues song, “Tight Like That,” which sold several million copies. The blistering pace of his life caught up with him; however, and he suffered mental distress. Only after seeking the counsel of a local Minister did he gain a measure of relief. More importantly, he also began to regain his religious and moral compass. Thomas Dorsey was to suffer at least two bouts of depression. Visits to Atlanta, where he also sought his mother’s counsel, helped him turn the tide. She encouraged him to come back to his spiritual roots.

blackartblog.blackartdepot.com/african-american-history/12-facts-about-thomas-dorsey.html

Thomas Dorsey blues career resulted in over 400 blues and jazz compositions and commercial success as a composer, arranger and touring blues artist. His adaptation of Piedmont style blues, ragtime, jazz and spirituals represented a transformation in the blues idiom. Blues became more rhythmic and syncopated, anticipating the birth of “Chicago Blues.” While enjoying the success of his blues career into 1930, Dorsey also began to write gospel music. His first gospel song, to achieve a measure of success, “If You See My Savior, Tell Him That You Saw Me’” was written in 1928, the same year that he collaborated with Tampa Red on “Tight Like That.” His efforts to make a living from writing “Gospel Hymns” did not meet with the success that he was achieving in Blues, but he continued to write gospel music, even while performing on the blues circuit.

Sometime later, he was introduced to a teenage prodigy at Chicago’s Greater Salem Baptist Church Choir, Mahalia Jackson. Mahalia joined Dorsey’s friend and subsequent business partner, Sally Martin, in demonstrating his songs at Chicago Churches. Dorsey’s big breakthrough in Gospel Music came in 1930 when Willie Mae Fisher sang his “If You See My Savior…” at the National Baptist Convention in Chicago. Rev. E. H. Hall, another “demonstrator” of Dorsey’s gospel compositions, rushed to tell Dorsey of her rendition. “She’s laying them out in the aisle and the folk are just jumping and going on. Man, you got to see them.”2 He reluctantly went, was encouraged to set up a booth and sold 4,000 copies of his sheet music.

The demand for his sheet music quickly spread to congregations throughout the South. Four major events occurred during in the next two years, in 1932: (1). Dorsey was asked by Rev. J. C. Austin to form a Gospel Choir at his Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago, (2). Founded the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses and (3). Established the first Gospel Music Publishing Company, Dorsey’s House of Music and (4th) tragedy struck.

During a gospel convention in St. Louis, Dorsey was called home because of complications with the delivery of his child by his wife, Nettie. Before he could make it home, he learned that Nettie had died, but his son, Junior, had survived. Once home, he was sedated and fell asleep. He was awakened by his uncle and was told that his son had died while he slept. Devastated by the loss of his wife and child, Dorsey again gave way to grief and despair. His friend, Rev. Theodore Frye, yet another “demonstrator” of Dorsey’s Gospel Blues, invited him to leave the house and go to a nearby beautician school which had a small room with a piano, an opportunity to get away and compose himself. While there, he sat down at his friend’s piano and the tears, pain and grief poured from him in song: 3 In an interview with Black World Magazine (precursor to Ebony Magazine), Dorsey said “…All the heart for writing gospel music went out of me during those hours of grief. I thought: ‘There ain’t no sense in trying to write songs of hope anymore. I ought to just go back into the blues business.’ But I didn’t. For, out of that awful trauma came the greatest song in my catalog. It happened like this: The late Professor Theodore Frye had a lovely music room here on what is now known as Dr. Martin Luther King Drive. You could go there and rehearse. He and I went up there one night not long after Nettie’s death. We just planned to go over some stuff. I began fooling around on the piano and a tune came to me. It was an old tune, but I found myself stumbling up on some new words which suited my mood of dejection and despair: Precious Lord–take my hand. Lead me on. Let me stand. I am tired. True I was so tired. I am weak. I am worn. Through the storm.

Through the storm. Plenty storm in my life now. Through the night. Hard night. Lead me on to the light. There had to be a light somewhere. There must be some happiness left somewhere. There must be success somewhere. Precious Lord. Take my hand. Lead me on.4

“Precious Lord, Take My Hand” became Mahalia Jackson’s signature song, one that she would sing for Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King in life and at his funeral. Dorsey and Mahalia toured together for many years. He wrote another song for her that she also would make her own, “Peace in the Valley.” It is no coincidence that the legacy of Thomas A. Dorsey as “Father of Gospel Music” directly intersected with that of Mahalia Jackson as “Queen of Gospel Music”

and Ma Rainey as “Queen of the Blues.” Add to this a veritable “who’s who” of early jazz and blues pioneers such as W.C. Handy, Joe “King” Oliver, Jelly Roll Martin, Kid Ory, Louis Armstrong, and Muddy Waters and it’s easy to see why the city of Chicago, between 1910 and 1940, indeed was the scene of an emerging, “Golden Era” of African American music.

Noted author and historian Lerone Bennett, Jr. in his seminal “Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America,” cites the three key pillars for the development and achievements of the African American community as the “black church,” fraternal lodges and “black colleges.” Among their earliest developments, he points to Reverend George Leile founding Savanna, GA’s “First African Baptist Church” in December of 1777, Rev. Richard Allen founding the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AMEC) in Philadelphia, PA in 1779, Prince Hall founding African Lodge # 459 in Boston, MA in 1787, and the initial charter of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZC) in 1801. Rev. Richard Allen became arguably the most influential leader of the African American community during the late 18th and early 19th century.5 In partnership with the Methodist Episcopal Church, the AMEC co-founded Wilberforce University in 1856. Closing temporarily during the Civil War, it was purchased by the AMEC from the MEC and reopened in 1863. Asa Philip Randolph, son of an AMEC Pastor, graduated from the Cookman School (now Bethune Cookman University) in 1907. W. C. Handy, “father of the blues,” was the son of an AMEC Pastor and grandson of an AMEC Pastor. These churches were the forerunners of the African American independent church.

Standing alongside the African American independent church was the twin pillar of “the invisible church” which was crucial to the slaves. Plantation masters reluctantly allowed slaves to practice their faith, but only under the watchful eyes of the slave masters. Missionary pastors were allowed to preach to slaves, but only so far as their “gospel” justified the slave condition and stressed obedience to the slave masters. Slaves also sat in the back of the slave masters churches, receiving the same message. This did not resonate with slaves. Although plantation owners forbade meetings among slaves without white supervision, they “stole way” to secret places during the dead of night, worshiping in what historians refer to as “hush harbors,” often deep in the woods, ravines or thick brush. They worshipped as they pleased, careful not to attract the attention of plantation masters at the risk of physical harm, even on pain of death. Their singing and dancing were integral in praise to a Creator who one day would end their suffering. Historians describe this “worship service” as a “ring shout,” hearkening back to the slave’s core, the rhythms and spiritual essence of Africa. When applied to their understanding of the Bible, they implored Divine Intervention or were resigned to deliverance through death; “Didn’t My Lord deliver Daniel…then why not deliver poor me…” or “Soon-ah will be done-ah with the troubles of the world…goin’ home to live with God…”

After Emancipation, many slaves joined AMEC, AMEZC and Baptist Churches; e.g., the invisible church of slavery was absorbed into the independent African American Church, comprised of the aforementioned church denominations and others, such as the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (CMEC) and, later, the Church of God in Christ (COGIC).

Harriet Tubman, a leader of the “Underground Railroad”, was born a slave circa 1821 in Dorchester County, Md. She escaped her captors in 1849, settling in Philadelphia. “Working as a domestic, she saved money until she had the resources and contacts to rescue several of her family members in 1850. This marked the first of 19 trips back into Maryland where Tubman guided approximately 300 people to freedom as far north as Canada. Maryland planters offered a $40,000 reward for Tubman’s capture at one point during her time as an Underground Railroad conductor.” See https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/underground/ny1.htm

She was a devout member of the AMEZC. “For over a hundred years, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church has been the steadfast guardian of the Harriet Tubman Home and the sacred grounds upon which it stands.” The AMEZC “…was the Freedom Church. In addition to the membership of Harriet Tubman, the church was the worship home for Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth as well.” Numerous African American Churches during the late 1700s through Emancipation had their basements configured secretively as a haven for escaped slaves embarked on the “Underground Railroad” seeking freedom and “Zion.”

African American Church Hymnody

AMEC founder Richard Allen published “A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns, selected from various authors” in 1801. “The first hymnal published with the intent to serve the black church, Allen sought to divert black worshipers away from the official Methodist hymnal. Within the first year, a second edition was published.” 6 The AMEC published its first hymn book in 1843; subsequent hymn books were produced in 1818, 1837, 1876, 1892, 1898, 1946, and 1954, culminating in the “Bi-Centennial Hymn Book” of 1984. 7

The AMEZ Church published its hymnals in 1839, 1858 1872, 1892, 1909, 1957 and 1997.8

The inaugural CME Church hymnal was published in 1891, followed by hymnals in 1904, 1939 (adopted in 1950) and 1987. The latter was an adaptation of the New National Baptist Hymnal of 1977.9

The Gospel Pearls was published by the National Baptist Convention Sunday School Publishing Board in 1921.10 Often cited by Thomas Dorsey as the hymn book that he most wanted to recognize his “gospel blues.” Ironically, his song “If I Don’t Get There,” already was included before he even began to market his Gospel Music to the National Baptist Convention in 1921. Like Allen’s hymnal of 1801, Gospel Pearls was a landmark publication in the history of African American hymnody.11 While the AME, AMEZ and CME hymnals drew heavily on the hymns of the English composers Dr. Isaac Watts and Samuel Wesley, the Gospel Pearls and, later, the New National Baptist Hymnal, also featured white gospel composers / songwriters such as Fanny Crosby (Near the Cross, Bless Assurance, Draw Me Nearer…), Elisha Albright Hoffman ( Glory to His Name, Leaning on the Everlasting Arms…), Charles Austin Miles (In The Garden…) and African American Composers / songwriters such as Thomas A. Dorsey, Charles Albert Tindley (Stand By Me, We’ll Understand it Better By and By…), and John Wesley Work Jr. (Director of the Fisk Jubilee Singers and Instructor at Fisk University, with his brother, Frederick Jerome Work; Gospel Pearls included Somebody’s knocking at Your Door, Swing Low, Were You There, and I Will Pray). 12

Exporting America’s New Music

“THEY that walked in darkness sang songs in the olden days—Sorrow Songs—for they were weary at heart. And so, before each thought that I have written in this book I have set a phrase, a haunting echo of these weird old songs in which the soul of the black slave spoke to men. Ever since I was a child these songs have stirred me strangely. They came out of the South unknown to me, one by one, and yet at once I knew them as of me and of mine. Then in after years when I came to Nashville I saw the great temple builded of these songs towering over the pale city. To me Jubilee Hall (at Fisk University) seemed ever made of the songs themselves, and its bricks were red with the blood and dust of toil. Out of them rose for me morning, noon, and night, bursts of wonderful melody, full of the voices of my brothers and sisters, full of the voices of the past…Little of beauty has America given the world save the rude grandeur God himself stamped on her bosom; the human spirit in this new world has expressed itself in vigor and ingenuity rather than in beauty. And so by fateful chance the Negro folk-song—the rhythmic cry of the slave—stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas. It has been neglected, it has been, and is, half despised, and above all it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.”13 So said W.E.B. Du Bois in his epic “The Souls of Black Folks” in 1903, in his poetic chapter entitled “The Sorrow Songs.”

A music that was borne of the slave regime, Lerone Bennet, Jr. observed that the expressions of the slaves evolved from “cries, hollers, work songs”…spirituals and blues, creating blues archetypes and spiritual archetypes. For Bennett, these blues and spirituals were indistinct from the slave world view, “that both the spirituals and the blues were products of a common blues-spiritual matrix. This totality, Americas only contribution to the world of music- was a collective product, but it was shaped by creative geniuses, by men and women of large visions and even larger voices, men and women immortalized by James Weldon Johnson in the poem, “O Black and Unknown Bards.”14

Bennett also observed that the most important achievement in the arts within the African American community during the late 19th Century was the export of Spiritual songs by the Fisk Jubilee Singers during their concert tours. “Important as these contributions were (in the arts), they were dwarfed in significance by public recognition of two prodigious contributions by the black masses. In 1870s and 1880s, well-mannered and well -scrubbed young men and women went out from Fisk University and sang the old spirituals and the world said that at long last America had created a new thing.

Go tell it on the mountain

Over the hills and everywhere,

Go tell it on the mountain,

That Jesus Christ is born

In the same years, but in different places and in different tones, grown men and women strummed guitars on the levees and in mean-looking bars or relieved their despair with cries and hollers in the cotton fields and on the chain gangs.

If I’d had my weight in lime,

I’d a whipped that captain

Till he went stone blind.”15

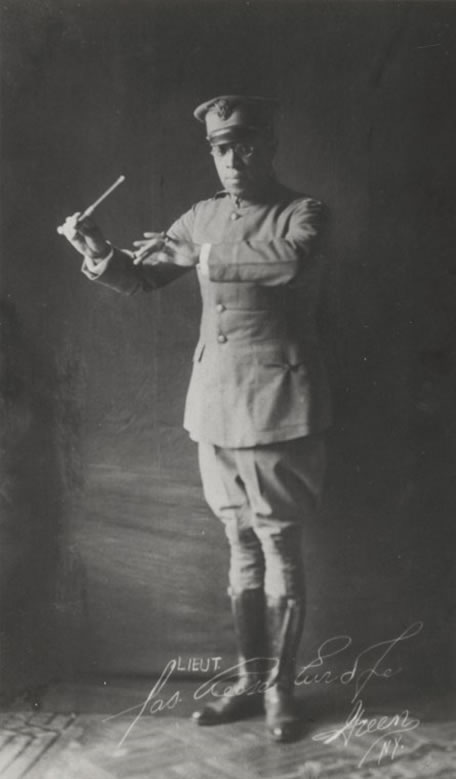

Lieutenant James Reese Europe

369th Regimental Band

James Reese Europe was born in Mobile, Alabama on 22 January 1881, but was raised in Washington DC from the age of 10. His mother was a pianist, and so he and siblings Mary and John also were formally trained in music, all becoming professional musicians. In addition to training at local DC schools, James Reese also took private lessons on violin under the tutelage of the Assistant Director of the U.S. Marine Corps Band. Reese relocated to New York in 1904 where he quickly ascended the ranks of Director / Composers and organized the Clef Club in 1910. It was both an organized labor for musicians and a source of bookings; the former was recognized by James Haskins in his Black Music in America as the first attempt to organize Black musicians. The Clef Club would also become a symphony Orchestra comprised of over 125 musicians and an institution supporting schools through fund raisers at Carnegie Hall. “Musical and social history were made on May 2, 1912, when James Reese Europe led the Clef Club Orchestra in a Carnegie Hall concert of marches, waltzes, liturgical music, popular songs and vaudeville tunes… The orchestra’s Carnegie Hall performance demonstrated a full spectrum of black music, from classical liturgical music and quasi-Viennese waltzes to small-group vaudeville numbers.

Part of the music looked toward European classical traditions, part toward American folk and pop songs; the original Carnegie Hall audience must have been thrilled to hear the hottest rhythms of the era – ragtime and a Latin maxixe. Frequently, the music evoked Scott Joplin, Johann Strauss and John Philip Sousa. Oom-pah, in various meters, was the order of the evening.”16

Europe later organized his “Society Orchestra” and composed music for the dance couple Vernon and Irene Castle, laying the ground for their introduction of the Fox Trot, Turkey Trot and the One Step to America; Haskins credits James Reese as the “inventor” of the Fox and Turkey Trots.17 Because of his association with the Castles, Europe’s band also would secure a recording contract from Victor Records, “the first ever given by a major label to a black orchestra.”18 The esteem with which Europe was held by fellow musicians clearly is evident by his recruitment of Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake to join his “Society Orchestra.”

After enlisting in the Army during World War I, Europe was asked by Colonel William Hayward to form the best military band in the Army. With the aid of funds from a patron of Col. Williams, Europe, with Sissle’s help, recruited some of the best musicians in America, even enticing a few from Puerto Rico and the Caribbean. The exploits of the 369th Regimental infantry Band became legend. “When the 369th and its band arrived in France, they were assigned to the 16th “Le Gallais” Division of the Fourth French Army because white U.S. Army units refused to fight alongside them. Trained to command a machine gun company, Europe learned to fire French machine guns and became the…first African American to lead troops in battle during the war.”

An account by the Drum Major of the 369th, Sergeant Noble Sissle, eloquently describes the impact of the music on France. Upon entering a town in France where few had ever heard “ragtime”, their audience included one American General and his family, some French Officers and the townspeople:

“The program started with a French march, followed by favorite overtures and vocal selections by our male quartette, all of which were heartily applauded. The second part of the program opened with ‘The Stars and Stripes Forever,’ the great Souza march, and before the last note of the marshal ending had been finished, the house was ringing with applause.”

“Lieutenant Europe, before raising his baton, twitched his shoulders, apparently to be sure his tight-fitting military coat would stand the strain, each musician shifted his feet, the players of the brass horns blew the saliva from their instruments, the drummers tightened their drum-heads, every one settled back in their seats, half closed their eyes, and when the baton came down with a swoop that brought forth a soul-rousing crash, both director and musicians seemed to forget their place, they were lost in scenes and memories. Cornet and clarinet players began to manipulate notes in that typical rhythm (that rhythm which no artist has ever been able to put on paper), as the drummers struck their stride, their shoulders began shaking in time to their syncopated raps.”

“Then, it seemed, the whole audience began to sway, dignified French officers began to pat their feet along with the American general who, temporarily, had lost his style and grace. Lieutenant Europe was no longer the Lieutenant of a moment ago, but once more Jim Europe, who a few months ago rocked New York with his syncopated baton. His body swayed in willowy motions and his head was bobbing as it did in days when tepsichorean (sic) festivities reigned supreme. He turned to the trombone players, who sat impatiently waiting for their cue to have a ‘Jazz spasm,’ and they drew their slides out to the extremity and jerked them back that characteristic crack.”

“The audience could stand it no longer, the ‘jazz germ’ hit them, and it seemed to find the vital spot, loosening all muscles and causing what is called in America an ‘Eagle Rocking Fit.’ There now, I said to myself, Colonel Hayward has brought his band over here and started ragtime in France, ain’t this an awful thing to visit upon a nation with so many burdens? But when the band had finished, and the people were roaring with laughter, their faces wreathed in smiles, I was forced to say this is just what France needs at this critical moment.” (Col. William Hayward, Commander of the 369th Infantry Regiment AKA Harlem’s acclaimed “Hell Fighters”)

“All through France, the same thing happened, Troop trains carrying Allied soldiers from everywhere passed us en route and every head came out of the windows when we struck up a good old Dixie tune. Even German prisoners forgot they were prisoners, dropped their work to listen and pat their feet to the stirring American music.”19

The Harlem Hellfighters would serve 191 days in combat, longer than any other U.S. unit, and reputedly never relinquished an inch of ground. The men earned 170 French Croix de Guerres for bravery. One of their commanding officers, Col. Benjamin O. Davis Sr., would become the Army’s first black general in 1940.

Europe was gassed while leading a daring nighttime raid against the Germans. While recuperating in a French hospital, he penned the song ‘On Patrol in No Man’s Land.’

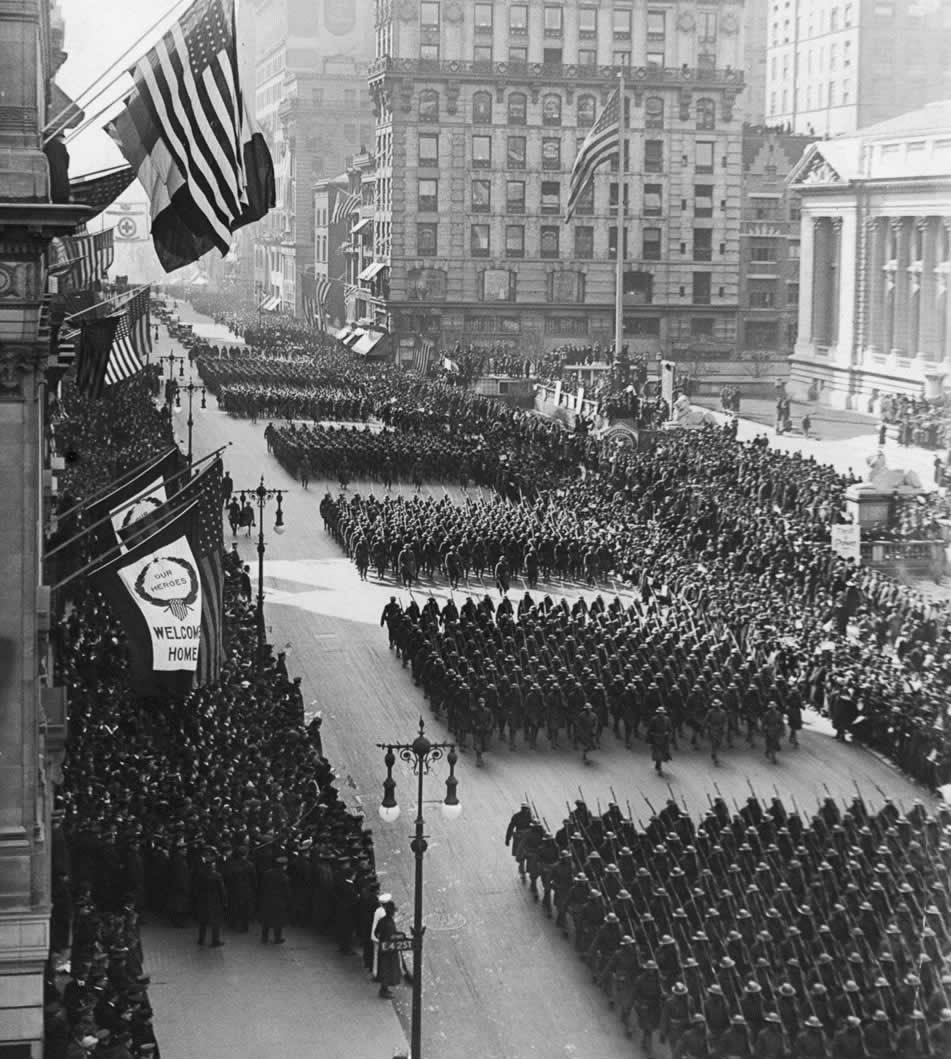

Europe and his musicians were ordered to the rear in August 1918 to entertain thousands of soldiers in camps and hospitals. They also performed for high-ranking military and civilian officials and for French citizens in cities across France. After Germany surrendered, the Hellfighters Band became popular performing throughout Europe. When the regiment returned home in the spring of 1919, it paraded up New York’s 5th Avenue to Harlem led by the band playing its raggedy tunes to the delight of more than a million spectators.”20 So wrote Rudi Williams, American Forces Press Services, for a Wreath Laying Ceremony for LT Europe at Arlington National Cemetery in February, 2000.

After a triumph return to New York after World War I, Reese’s life was cut short in May 1919, at the age of 39; his brilliant life extinguished at the hands of a former musician that he had let go. America and the world were deprived of a genius whose further contributions can only be imagined.

Lieutenant Europe’s right-hand man and Drum Major, Sargent Noble Sissle, was promoted to Lieutenant at war’s end. He would later collaborate again with the legendary Eubie Blake to create the ground-breaking musical “Shuffle Along,” then both enjoyed legendary careers among the pioneers of Jazz. Thomas A Dorsey fondly recalls Chicago’s music scene in 1925, where “I had great experiences in the heyday of the old Grand Ballroom when the jazz immortals, that’s what they are now, came through, doing their thing. It was there my friendship began with Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake. There are two grand guys. I guess if they can carry on as well as they do at 79 and 80 years, I can make it on through some more years, being my youthful 75.”21

Appendix I

James Reese Europe Timeline: Both of Direct and Indirect Significance

1863

1 January: President Abraham Lincoln implements the Emancipation Proclamation.

1865

18 December: The 13th Amendment is officially adopted into the Constitution of the United States, abolishes slavery.

1866

2 December: Harry T. Burleigh is born in Erie, PA. Burleigh became an assistant to and lifelong friend of Antonin Dvorák while a student at the conservatory of Music in New York. His demonstration of African American Spirituals to Dvorák vocally and on piano influenced the legendary composer’s adaptation of original American Music to symphonic composition. “Dvorák’s use of the spirituals “Goin’ Home” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” in his Symphony no. 9 in E minor (“From the New World”) was probably influenced by his sessions with Burleigh.” Owing to the encouragement of Dvorák to embrace his knowledge of these African American spirituals in the development of Burleigh’s own compositions, he published over 300 (Paul Finkelman, 2004)songs in the genre that is known as “American art songs.” Upon his death in 1949, his funeral was attended by over 2,000 people at St. George’s Episcopal Church where he had served as soloist for over 50 years. His pallbearers included Eubie Blake, W.C. Handy and Noble Sissle.22

1868

Robert Allen Cole (Bob Cole) was born on July 1, 1868, in Athens, Georgia, the son of former slaves. Like Will Marion Cook and James Reese Europe, he became one of the most important composers of his generation, creating a model for other African-American musicians and composers.

1869

27 January: Wil Marion Cook was born in Washington, D.C. His father, John Hartwell Cook, was in the first class of students at Howard University Law School in Washington, D.C., later becoming the school’s first Dean. One of the most important figures in pre-jazz African-American music, Cook was a composer, conductor, performer, teacher, and producer. He was involved in numerous areas of African American music during the late 19th and early 20th century; worked with most of the extraordinary musicians of the period. When he was 15, Cook studied violin at Oberlin College. Frederick Douglass

- helped organize a fundraiser to send Cook to study in Europe. As a result, Cook studied from 1887-89 at the “Berlin Hochschule für Musik” with Joseph Joachim, the famous violinist and associate of Brahms. Writing music with the great poet Paul Laurence Dunbar as lyricist, and teaming up with the superb musical performers Bob Cole, George Walker, and Bert Williams, Cook arranged orchestration and wrote lyrics and songs for the best musicals of his generation.

- 3 July: Violinist Joseph Douglas, grandson of Frederick Douglas, was born in the Anacostia section of Washington DC.

1871

17 June: James Weldon Johnson was born in Jacksonville, FL He was a legendary songwriter, author, diplomat, and activist. In short, Johnson was one of the preeminent personalities of the “Harlem Renaissance.”

1872

27 June: Paul Laurence Dunbar, poet, novelist and play right, was born in Dayton, OH. He moved to Washington DC and accepted a job with the Library of Congress as an assistant for research in 1897. Judge Robert H. Terrell, husband of women’s suffragist and NAACP co-founder Mary Church Terrell wrote a letter to his father-in-law on December 3rd, 1897… “My Dear Mr. Church, we have succeeded in renting your house to Paul Laurence Dunbar, whom Mrs. Church and you know well…”23 Judge Terrell was named Principal of the M Street High School in 1899, Mary Terrell taught there between 1887and 1891. When the school was rebuilt in 1916, it was renamed in honor the late poet “Paul Laurence Dunbar High School.”

14. 1934 – 1936 – 1938 4th Street

Robert and Mary Church Terrell lived at 1936 (in the middle) and Paul Laurence Dunbar lived at 1934 (on the left)

1873

- 6 May: Fisk Jubilee Singers depart Nashville and embark on their first European Tour, initially performing in England, followed by concerts in Scotland, Ireland and Wales. “By the end of the European campaign, the troupe raised nearly $50,000 for the construction of Jubilee Hall, which became the first permanent structure on the campus of the Fisk School…After seven years of travelling throughout Europe, the Jubilee Singers were able to give $150,000 to Fisk University.”24

- August 11: John Rosamond Johnson was born in Jacksonville, FL. He began studying music at the age of 4, received instruction at the New England Conservatory and from Samuel Coleridge-Taylor in London. At the turnoff the twentieth century, he composed Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing, regarded by many as the African American National Anthem. Johnson collaborated with his brother, James Weldon Johnson, and Bob Cole to become one of the preeminent team of songwriters and composers leading up to “The Harlem Renaissance.”

- 16 November: William Christopher (W.C.) Handy was born in Florence, AL. His father and grandfather were pastors in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AMEC); regarded by many as the “Father of the Blues.” In addition to publishing numerous blues standards, he published W. C. Handy’s Collection of Negro Spirituals in 1938 through his publishing company, “Handy Brothers Music, Co. in New York.25

1881

James Reese Europe was born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1881, Europe’s family moved while he was young to Washington, D.C. In 1904 he moved to New York City, starting out as a pianist. Eubie Blake said of James Reese Europe, “He was our benefactor and inspiration. Even more, he was the Martin Luther King of music.”

1888

Wil Marion Cook graduates from Oberlin College. His first recital after returning to Washington DC was sponsored by Frederick Douglas.

1892

Internationally acclaimed Bohemian composer Antonin Dvorak becomes Director of New York’s National Conservatory of Music. Burleigh receives a scholarship to attend the Conservatory the same year.

Chicago World’s Fair (The Columbian Exposition of 1893):

- The Chicago World’s Fair attracted offer 27 million visitors from May to October. It featured exhibitions from over 46 countries and celebrated the new inventions of America, innovative architecture and the best of American culture. Advances in social reform were not yet on display.

- Scott Joplin brings his “Texas Medley Quartette” to Chicago, playing in saloons and joints on the periphery of the fair grounds. African Americans were not given an opportunity to showcase their talents in a dedicated venue at the Fair, with one major exception.

- The government of Haiti appointed Frederick Douglas as the co-commissioner of its delegation, allowed Douglas the use of their Haitian Pavilion.

- – Douglas was accompanied by his grandson, violinist Joseph Douglas, and Composer and violinist Wil Marion Cooke.

- – Douglas befriends Langston Hughes, gives him a job at the Haitian Pavilion. James Weldon Johnson also participated in the Fair, joining many college students who were part time employees.

- Douglas speaks to over 2,500 attendees of the “Colored American Day” in August at the Colombian Exposition Festival Hall. Wil Marion Cook and Joseph Douglas provided music after the Douglas speech, Langston Hughes recited poetry. The Cook and Hughes collaboration may have been among their first, with many to follow.

- November: Premier of Antonin Dvorak’s Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, “From the new World.” Shortly after the premier, “Thomas Burleigh and Sissieretta Jones (Black Patti) would quickly become featured soloists under Dvorak’s direction.”26

1894

James Weldon Johnson graduated from Atlanta University.

1895

The Honorable Frederick Douglass dies at his Cedar Hill home in Anacostia, Washington DC on 20 February. His funeral was held at the Metropolitan A.M.E. Church in DC on 25 February. Over 25,000 mourners lined the streets along the funeral procession from his beloved Cedar Hill estate to the A.M.E. Church. Mourners continued to crowd into the overflowing throng until the doors were closed for the solemn service. Scores of prominent Religious and political officials, entertainers and social activist were in attendance. Rev. Dr. J.T Jenifer, Pastor of Metropolitan A.M.E. Church presided; Rev. Alexander Walker Wayman, Seventh Bishop of the A.M.E. Church, Rev. Dr, J.W. Hood, Senior Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) Church, Dr. Jeremiah Rankin, Sixth President of Howard University and author of “God Be with You ‘Til we Meet Again” and “Tell It to Jesus” and Susan B Anthony, President of the National Women Suffrage Association also spoke remembrances and tributes to Douglass. Honorary Pall

Bearers included former Mississippi Senator Blance Kelso Bruce, second African American Senator and first to be elected to a full term, former Mississippi Congressman John R. Lynch, one of the most successful African American Congressmen in the Reconstruction South, served three terms and P.B,S Pinchback, former Governor of Louisiana, first African American Governor in American history.27

1898

Premier of Clorindy, the Origin of the Cakewalk (1898), the first African American musical composed by African Americans with an all African American cast. The music was composed by Bob Cook; Paul Laurence Dunbar was the lyricist and librettist. According to James Weldon Johnson, it “was the first demonstration of the possibilities of syncopated Negro music.”28

1899

Scott Joplin composes his ragtime musical, Maple Leaf Rag29

1900

- J Rosamond Johnson writes the music for “Lift Every Voice and sing,” his brother, James Weldon, writes the lyrics. The Jonson Brothers move to New York.

- Harry T. Burleigh became the first African-American soloist at New York’s Temple Emanuel-El where he served for 25 years, arranged “Deep River,” an African-American spiritual, for their church choir

1902

Scott Joplin composes his ragtime hit, The Entertainer30

1904

Europe moves to New York. (LOC)

1907

Bob Cole wrote the musical “The Shoo-Fly Regiment,” J Rosamond Johnson wrote the music, lyrics provided by James Weldon Johnson, conducted by James Reese Europe.

1908

ob Cole and J Rosamond Johnson produce the musical “The Red Moon: An American Musical in Red and Black,” choose James R. Europe as conductor.

1909

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded in New York. Founding members included African American activists W.E.B Dubois, Women’s Suffragist and Civil Rights Activist Mary Church Terrell, and social/political activist Ida Wells-Barnett.

1910

“Europe formed the Clef Club and became its president. This organization not only put together its own orchestra and chorus, but served as a union and contracting agency for black musicians. Soon it had as many as 200 men on its roster. On May 2, 1912, the Clef Club Symphony Orchestra put on “A Concert of Negro Music” in Carnegie Hall. The concert was a tremendous success. The 125-man orchestra included a large contingent of banjos and mandolins and presented music by exclusively black composers.”

1912

- William Christopher Handy writes and publishes “Memphis Blues.”

- April: first of 4 concerts for the benefit of the Music School Settlement for Colored people performed at New York’s Carnegie Hall. “Thomas “Burleigh served on the original Board of Directors (for the school)…with Natalie Curtis, W.E.B. du Bois, (David) Mannes (violinist) and his wife, Lyman Beecher Stowe (grandson of Harriet Beecher Stowe and others…” P 128 Jean Snyder. James Reese Europe and his Clef Club Orchestra performed.

1913

- Burleigh sings “Calvary” at the funeral of John Pierpont (JP) Morgan, legendary financier and banker, on 14 April New York’s ST. George Episcopal Church. Burleigh sang “Calvary” at the special request of the late Morgan.31

- Harry H. Pace, former business partner and student of W.E.B Du Bois, and W. C. Handy form Pace & Handy Music Company; as operators of the company, “W. C. Handy and Harry Pace would make Memphis the capital of the nation’s published blues music from 1914 to 1918.”32

1914

- C. Handy writes and publishes “St. Louis Blues.”

Burleigh and Will Marion Cook establish a choral society in association with the Music School Settlement for Colored People. In their 3rd benefit concert at Carnegie Hall, Burleigh conducts their chorus of eighty voices performing his “Deep River” and “Dig

- My Grave.” He also sang three spirituals, “I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired,” “Bury Me in De Eas,’ ” and “Weepin’ Mary.” Cook’s Afro-American folk Singers sang four of his signature songs, “Rain Song,” “Swing Along,” “Exhortation,” and “a Negro Sermon.” James Reese Europe’s Negro Symphony Orchestra also played arrangements of Burleigh’s compositions. According to a New York Times Review, “The fact that the programme consisted largely of plantation melodies and spirituals, which were in each case ‘harmonized, ’arranged,’ or ‘developed,’ showed that these composers are beginning to form an art of their own on the basis of their folk material.” 33

1916

James Reese Europe enrolls in the 15th Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard, followed shortly by Noble Sissle. Europe was commissioned a 1st Lieutenant in the Army at year’s end.

1917

- Europe is asked to organize and recruit for the 15th Infantry Regimental Band; travels to Puerto Rico and returns to New York with approximately 18 musicians, many of whom were reed and brass players. Among the most notable was Rafael Hernández, legendary Puerto Rican composer and song writer who enlisted as a “Band Sargent.”

- In her History of High School for Negroes in Washington (M Street School), Mary Church Terrell says of one of their distinguished graduates, “James Reese Europe is a composer of distinction and the leader of an orchestra which is constantly in demand among the most cultured and the wealthiest people of New York.” 34 (Mary Church Terrell was the daughter of the legendary Memphis entrepreneur and philanthropist, Robert Reed Church, Sr., wife of former M Street School Principal and Washington DC Judge Robert Terrell, charter member of the NAACP and legendary women’s suffragist)

- 2 May: Europe returns to New York after spending 3 days in San Juan, Puerto Rico with at least 12 Puerto Rican musicians, recruited for his 15th Regiment Band; some sources cite as many as 18.

- 15 July: 15th Regiment ordered into active service.

- 5 August: Lieutenant James Reese Europe receives commission in the U.S Army.

September: W. C. Handy takes his “Handy’s Orchestra of Memphis” to New York City for recording sessions with Columbia Records. “Yet for Handy both professionally and historically, this New York City trip was most significant for his first meeting with James Reese Europe, the adapter of ‘The Memphis Blues.’ By the autumn of 1917, Europe had accomplished far more than W. C. Handy in bringing African American music to a national white audience…” When told of Reese’s tragic death less than two years later,

- “Handy was sincerely shaken by his younger rival’s murder. …he did not sleep that night, ‘Harlem did not seem the same’…”35

- 8 November: 15th Regiment Band marches in parade and performs concert in New York’s Central Park.

- 12 December: 15th Infantry Regiment sails for France, arrives on 1 January, 1918.

1918

- C. Handy and the “firm of Pace & Handy moves to New York City.”36

- 12 February to 20 March: 15th Infantry Regiment conducts concerts throughout France.

- 12 March: the 15th Infantry Regiment is re-designated the 369th Infantry Regiment, sent to the “front” under the command of French Forces.

- Mid-March to August: Lt Europe deploys to the front lines with the 369th

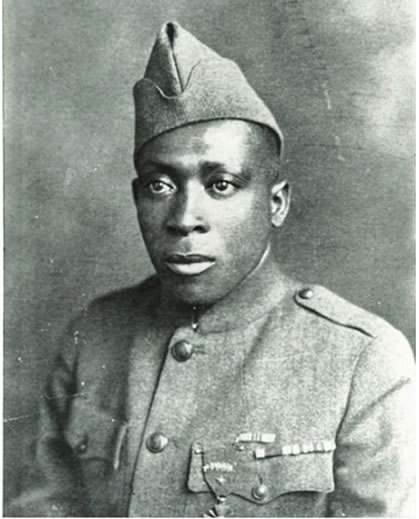

- 15 May: Privates Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts, of the 369th, while on sentry duty, fight off a German attack against over 20 enemy soldiers; recognized for gallantry by General John J. Pershing in a cable to the Army Chief of Staff in Washington on 20 May, 1918.

- June to July: Europe wounded in gas attack, hospitalized. Writes and composes the song “On Patrol in No Man’s Land” from his hospital bed. “Today, the Purple Heart may be awarded to any soldier who, while serving under competent authority in any capacity with one of the Armed Forces after 5 April 1917, is killed or wounded in any of the following circumstances: In action against an enemy of the United States; In action with an opposing armed force of a foreign country in which the Armed Forces of the United States are or have been engaged…” Given the above, Lieutenant James Reese Europe is much deserving of a posthumous award of the Purple Heart, though I’ve seen no evidence that he has received one.

- Early July to Early August: Lt Europe enjoys convalescent leave, then returns to lead the 369th Regimental Band.

- 11 November: World War I ends (Armistice Day).

- 11 December: “… the French government bestowed one of its highest military awards on Europe and the 369th Infantry. The Dec. 9, 1918, citation to the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Star reads in part: This officer ( James Reese Europe), a member of the 369th Infantry Regiment of the 93rd Infantry Division, American Expeditionary Forces, was the first black American to lead United States troops in battle during World War I. The unit, under fire for the first time, captured some powerful and energetically defended enemy positions, took the village of Bechault by main force, and brought back six cannons, many machine guns and a number of prisoners’.” After their wreath-laying ceremony (on 5 June 2000), the legionnaires attended a jazz concert performed by the Army Band’s jazz ensemble at Fort Myer, Va., in Europe’s honor.”

Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Harlem Hellfighters shown pictured wearing their “French Croix de Guerre” Medals

Henry Johnson was one of the heroic soldiers of the Harlem Hellfighters, lost in history until Senator Chuck Shuman remedied the situation by spearheading the drive to honor Johnson posthumously with the Medal of Honor, America’s highest military award, presented by President Barack Obama in a White House ceremony on 2 June, 2015.

“While on patrol in a French forest in 1918, the then-private single-handedly fended off an attack from two dozen German soldiers, defending himself and his wounded fellow sentry with his gun, then a club, then nothing but a bolo knife and his bare hands. Johnson’s grit saved him and his partner from being taken prisoner and prevented the Germans from breaking the French line.

Briefly, he was showered with glory. The French gave him the Cross de Guerre avec Palme, their highest award for valor. His ribbon also featured a golden palm for “extraordinary valor;” he was the first American to receive this high honor from the French government. President Theodore Roosevelt called him one of “the five bravest Americans” to serve in World War I. The U.S. Army even used his image to sell victory stamps (“Henry Johnson licked a dozen Germans. How many stamps have you licked?” the advertisements asked). His admirers called him “black death” and filled the streets to cheer his regiment on their return…”

Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

https://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=42675

Historic Marker in Albany, NY: The Battle of Henry Johnson

1919

- 12 February: The 369th returns to New York City

- 17 February: the 369th is honored with a parade in New York City, led by the band and James Reese Europe.

- 25 February: Europe honorably discharged from the U.S. Army.

- 16 March: The 369th Band begins a 10-week tour of the East and mid-West.

- 9 May: Europe is stabbed by a former band member, dies from his wounds. The tragic incident was witnessed by Noble Sissle and legendary African American Tenor Roland Hayes, who had gone back stage to greet and congratulate Europe following his band’s concert performance.37

- Noble Sissle writes in his memoirs, after a young hospital orderly “…softly whispered ‘Lieutenant Europe is dead.’ Those words are still ringing in my ears! Dead! Jim Europe, who had survived dangers, operations! Jim Europe, who had been through the living hell of the late war! He, who escaped the missive of death hurled at him and others by a perilous enemy had fallen by the hand of an assassin! One whom he had taken from the gutters of New York and brought fame and glory…The band played the next morning on the steps of the Capital (Boston, Mass). Governor Coolidge (Calvin) presented it with ‘a’ wreath, but that wreath, instead of being placed upon the monument of Robert Gould Shaw, was placed as a token of respect and patriotic appreciation by the governor of Massachusetts and the commonwealth upon the bier of Lieutenant Jim Europe,” in Sissle’s words, ‘America’s first jazz king’. “38

- 13 May: Europe is honored with the first public funeral for an African American in New York. Sissle goes on to observe, “There followed a funeral the like of which has never been seen to move through the streets of New York, and impressive ceremonies, which were attended by man scions of society, and the rank and file of all races and creeds, who at some time, had sat beneath the spell of that baton that had rocked the world in his syncopated movement. Interment was made at Arlington Cemetery, Washington, D.D, where the earthly remains of this war-hero lies alongside of those of the other patriots whose deeds of glory have emblazoned the pages of American History.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eC9m3Xie3uk

Video: James Reese Europe the Hellfighters

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3AoQqTYjFSA

Video: Blues America Parts 1 and 2

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2MVmxJ6q0JM&list=PLOn32a3nEC1nGfUJodMg399K85IGhV1Bk&index=3

Video: Alex Rudison performs Gradus ad Parnassum

Bibliography

Badger, R. (1995). A Life in Ragtime. New York: Oxford University Press.

Badger, R. (2009). James Reese Europe. Encylopedia of Alabama, 1.

Chernow, R. (2010). The House of Morgan: An Amercian Bankng Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. New York: Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Christopher A. Brooks, R. S. (2014). Roland Hayes: The Legacy of an American Tenor. Bloomington: Inidana University Press.

David Malone. (2010). Gospel Pearls. ReCollections, Wheaton College Special Collections, 1.

Douglass, H. (1897). In Memoriam: Frederick Douglass. New York: J.C. Yorston & Company.

Du Bois, W. E. (1903). The Soul of Black Folks. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co.

Duckett, A. (1974). An Interview With Thomas Dorsey. Black World/Negro Digest, 96.

Foley, E. (2000). Worship Music. Collegeville: Liturgical Press.

Frazier, E. F. (1964). The Negro Church in America. New York: Shocken Books, Inc.

Gioia, T. (2011). The History of Jazz, 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Handy, W. C. (1938). W.C. Handy’s Colletion of Negro Spirituals. New York: Handy Brothers Music Co.

Harris, M. W. (1992). The Rise of Gospel Blues: The Music of Thomas Andrew Dorsey in the Urban Churh. New York: Oxford University Press.

Haskins, J. (1987). Black Music in America: A History Through Its People. New York: Harper Trophy.

Johnson, C. (2007). Forgeries of Memory and Meaning: Blacks and the Regimes of Race in American . Chapel Hill: Universty of North Carolina Press.

Lerone Bennett, J. (1861,1962, 1964, 1969, 1982). BEFORE THE MAYFLOWER: A History of Black America, Fifth Edition. New York: Pengun Books.

Lerone Bennett, J. (1984). Before The Mayfower: A History of Black America, Fifth Edition. New York: Penguin Group.

Pareles, J. (1989, July 17). Review/Music; Re-creating a Night When History Was Made. The New York Times, p. Arts.

Paul Finkelman, C. D. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance: K-Y. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Rudison, R. (2016). American Blues, Jazz & Soul Food. Bloomington: AhthorHouse.

Scott, E. J. (1919). Scott’s Official History of the Negro in the World War. Boston: Homewood Press.

Sissle, N. (1942). Memoirs of Lieutenant”Jim” Reese Europe. Washington D C: Library of Congress.

Snyder, J. E. (2016). Harry T. Burleigh: From the Spiritual to the Harlem Rensassance. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Southern, D. E. (1997, 1983, 1971). The Music of Black Amercians: A History, 3rd Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Spencer, J. M. (1990). The Hymnody of the Arican Methodist Episcopal Church. JSTOR, 274-293.

Terrell, J. R. (1897, December 3rd). Letter to Robert R. Church. Washington, DC, USA: Self.

Terrell, M. C. (1917). History of the High School for Negroes in Washington. JSTOR, 252-266.

Townsend, W. A. (1921). Gospel Pearls. Nashville: Sunday School Pub. Board, National Baptist Convention of America.

Williams, R. (2000). James Reese Europe: First Lieutenant, United States Army. Arlington: ArlingtonCemetery.Net.

Illustration I

Illustration II

Illustration III

1(Rudison, 2016), Introduction

2Michael Harris, The Rise of Gospel Blues, p. 176

3Ibid,

4 (Duckett, 1974)

5(Lerone Bennett, 1861,1962, 1964, 1969, 1982)

6(David Malone, 2010)

7(Spencer, 1990), P 225

8Ibid

9Ibid

10(David Malone, 2010)

11(Southern, 1997, 1983, 1971)

12(Townsend, 1921)

13(Du Bois, 1903),

14(Lerone Bennett, Before The Mayfower: A History of Black America, Fifth Edition, 1984), p. 102-103

15Ibid

16(Pareles, 1989)

17(Haskins, 1987), p 52

18(Badger, James Reese Europe, 2009)

19(Scott, 1919), Chapter XXI

20(Williams, 2000)

21(Duckett, 1974)

22(Paul Finkelman, 2004)

23(Terrell J. R., 1897)

24(Jackson, 2004), Page 2

25(Handy, 1938)

26(Snyder, 2016), P. 145

27(Douglass, In Memoriam: Frederick Douglass, 1897)

28(Johnson, 2007), p 154

29(Robertson, 2009), page 79

30Ibid

31(Snyder, 2016), p 219

32(Robertson, 2009), Pages 12 and 147

33Ibid, 129

34(Terrell M. C., 1917)

35(Robertson, 2009), pages 168-171

36(Robertson, 2009), p. 171

37(Christopher A. Brooks, 2014), p 48

38(Sissle, 1942)